After leaving the little round Earth last week, the Artemis I’s Orion spacecraft had a successful flyby of the moon early Monday morning.

What You Need To Know

- Artemis I's Orion spacecraft will start its flyby of the moon at 7:26 a.m. EST

- You can track the Orion's mission live right here ▶

- RELATED coverage: Despite delays, NASA launches Artemis I to the moon

- Learn more about the Artemis mission here ▶

- 🔻Scroll down to watch the flyby🔻

- Learn more about the Artemis mission here ▶

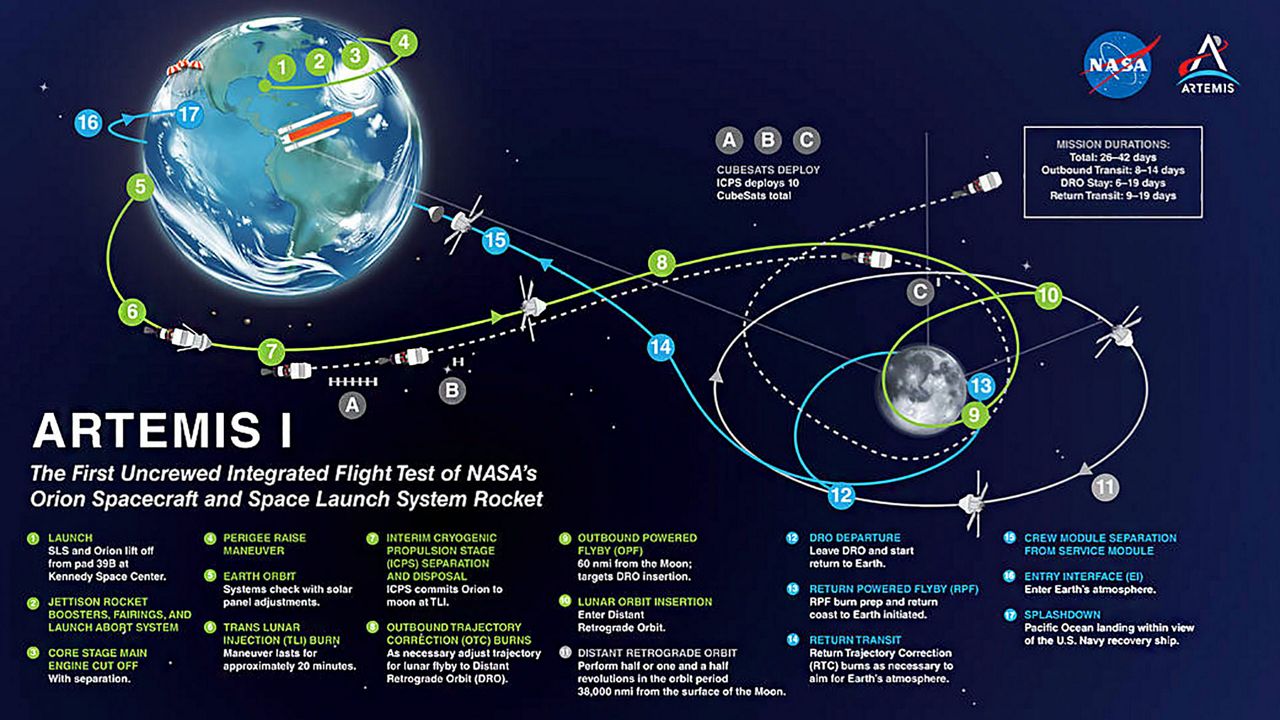

After numerous delays because of liquid hydrogen leaks and hurricanes, on Wednesday, Nov. 16, NASA made history once again by launching the Artemis I mission and ushering in a fresh course that will allow humankind to return to the moon.

And on Monday, Nov. 21, all the hard work paid off as NASA covered the historic moment live on its website.

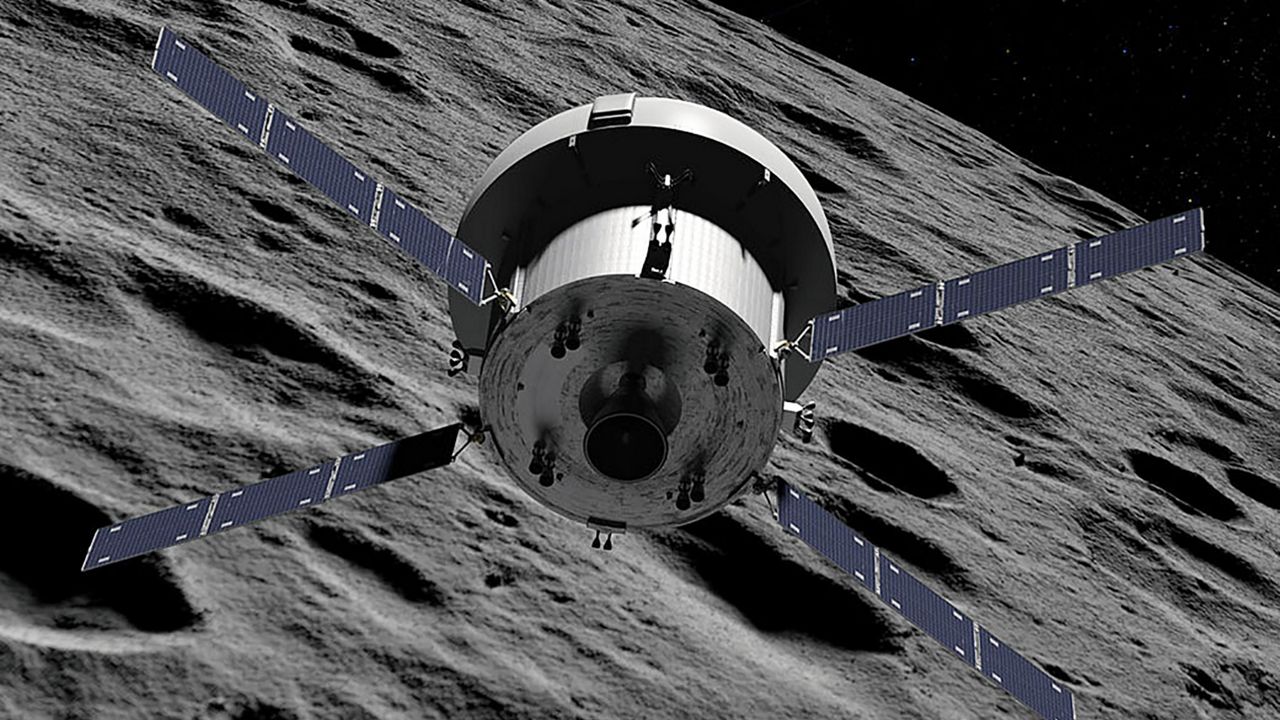

At around 7:44 a.m., the uncrewed Orion began its flyby as the nearly 11-foot-tall spacecraft went behind the moon.

From 7:26 a.m. EST to 7:59 a.m. EST, the little craft that will one day hold four people lost contact with its creators as it made its closest approach — about 80 miles — above the lunar surface at around 7:57 a.m. EST. NASA had originally stated that the closest Orion would be from the moon was 60 miles.

Communications resumed once Orion was no longer behind the moon, confirmed Sandra Jones of NASA’s communications during the live telecast.

While Orion was making this approximately 1,300 mph flyby, it was about 238,900 miles away from Earth. Now, it is on its way home.

The entire flyby was met with a mixture of anticipation — when there was no communication between Orion and NASA — and excitement.

“This morning we just saw the Earth set behind the moon as we take the next human-rated vehicle around the moon, preparing to bring humans back there within a few years. This is a game changer,” said Zebulon Scoville, NASA’s flight director during the space agency’s live telecast.

The last time a vehicle that could hold people orbited the moon was in December 1972 during Apollo 17. Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt walked on the lunar surface while Command Module Pilot Ronald Evans was in orbit.

Smile for the camera

Flight controllers have already tested Orion’s four solar arrays to examine the WiFi signal strength and which configurations for the arrays work best to get the most out of them.

The reason for this is to determine which position is best to transfer photos from Orion back to Earth.

Between Orion and its former companion — the 322-foot-tall Space Launch System rocket that hurled the spacecraft from Launch Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center to the moon — there are a total of 24 cameras.

Eight on the Space Launch System rocket and 16 on the Orion spacecraft. NASA described these cameras as important to the Artemis I mission as they “… document essential mission events including liftoff, ascent, solar array deployment, external rocket inspections, landing and recovery, and capture images of Earth and the moon.”

The mission is more than just a flyby

While flying around the moon is a feat in itself and certainly, a moment that many have looked forward to, the real test behind the Artemis I mission is the reentry of the Orion and checking its heat shields.

“Engineers intend to learn as much as possible about Orion’s performance during the flight test and are focused on the primary objectives for the mission: demonstrating Orion’s heat shield at lunar return re-entry conditions, demonstrating operations and facilities during all mission phases, and retrieving the spacecraft after splashdown,” NASA stated.

And not just heat shields, but other systems are being looked into. As mission managers and engineers are focusing on Orion’s flyby, NASA has two active anomaly resolution teams.

These teams will focus on issues that have come up on Artemis I’s journey so far: An unknown number of faults have come up in the random access memory of the star tracker system, but the information has been recovered.

And another issue has come up: “ … one of eight units located in the service module that provides solar array power to the crew module, called a power conditioning and distribution unit umbilical latching current limiter, opened without a command. The umbilical was successfully commanded closed each time and there was no loss of power flowing to avionics on the spacecraft,” NASA confirmed.

However, NASA assured that both systems are working now and these issues have not affected the mission.

Once the Orion returns to Earth in the Pacific Ocean on Dec. 11, 2022, in a splashdown, scientists and engineers will unwrap the Artemis I mission’s findings. These discoveries will lay the groundwork to make possible improvements to prepare for the next mission: the Artemis II, where astronauts will do a flyby of the moon in 2024.