ORLANDO, Fla. -- It's a $2.7 million dollar grant to help University of Central Florida researchers with a big mission: use technology to improve children's speech, then codify guidelines for an entire industry.

- Joey Genovesi utilizes UCF’s clinic for speech impaired son

- Technology used to assist children with speech

- UCF to offer five year free trial to parents

"I think it's amazing because people need this resource, parents we need this resource, the kids need this resource," said Joey Genovesi.

Twice a week, the father brings his 5-year-old son, Alejandro, to therapy at UCF's Florida Alliance for Assistive Services and Technologies, or FAAST, Clinic to work on his speech. His son says he's headed "to work."

"It had started to affect his learning capabilities. His teachers weren't understanding him, so they were assuming he wasn't getting it," Genovesi explained.

But, the father said that Alejandro was getting it. He just wasn't communicating what he wanted to say, leading to frustration.

"He would shut down … you could see the tears in his eyes," the father said. "We added medical therapy then we changed schools. Then we changed schools again, then we found this."

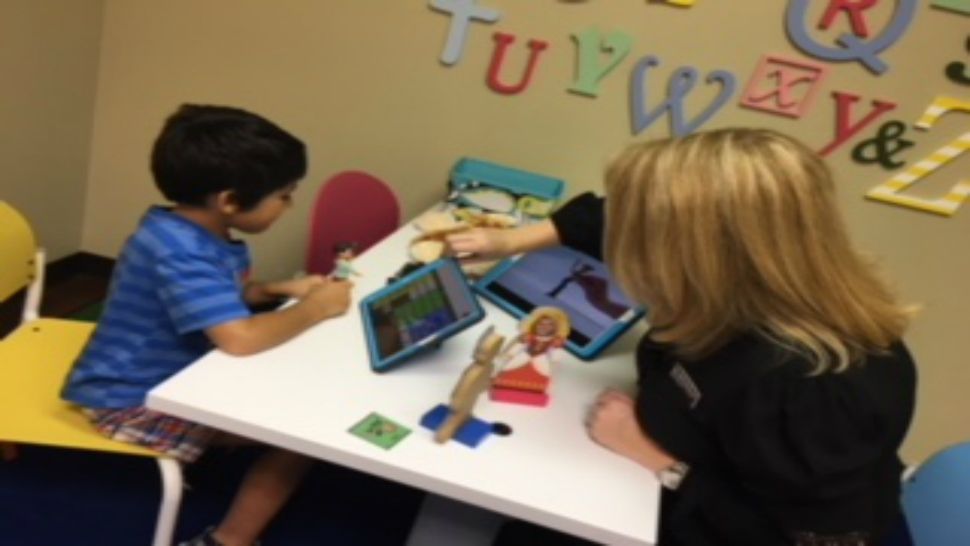

From another room at the FAAST Clinic, headphones on and staring at a computer monitor, Genovesi can watch his son without impeding on the lesson. Inside a colorful playroom, Alejandro works with student clinicians using sensory toys and a variety of apps.

"They don't have time to waste, these kids. So we want them communicating at the level they should be for their age," said Jennifer Kent-Walsh, UCF Professor of Communication Sciences and Disorders. "There's a lot of frustration that comes out when they know what they want to say, that's not the issue. But they just don't have a way to deliver that message."

For the last 15 years, Kent-Walsh said that the clinic has examined different ways in which children could learn and improve their natural speech using apps.

The center also provides services for young adults, adults and the geriatric population.

And while there are plenty of apps which help, guidelines for speech pathologists, teachers and family members to use them are nonexistent.

"That's what we're trying to do here in our research. Focus in and provide very clear guidelines," she said.

So, Kent-Walsh and her team applied for a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Awarded the $2.7 million grant in July, alongside the University of New Mexico, they are now looking to enroll 120 participants -- 3- to 4-year-old children -- in Central Florida for a five-year clinical trial.

The trial is free for the families who participate; the university said that they will receive some compensation.

“We were really stunned. We were so excited to be at that point to finally be able to implement a clinical trial on a grand scale," she said.

The goal, according to Kent-Walsh, isn't to create dependency on technology. Rather, to help children communicate more effectively.

"Over time, in many cases, they use the technology less as their speech improves," she said.

"We've had many examples of children telling their parents that they love them for the first time. That they haven't been able to do that.”

As for her patient Alejandro, he won't be able to take part in the latest clinical trial. He's too old.

Yet, the researcher said that he's thriving.

"Incredible progress absolutely, both in using the technology and then hearing it in his natural speech," she said.

His father agreed: "He’s come out of his shell."