YBOR CITY, Fla. — For more than three decades, the political leadership in Hillsborough County chose not to raise impact fees on developers to pay for infrastructure, but the political winds are blowing fiercely in the opposite direction in 2020.

- Democrats now hold majority on County Commission

- Impact fees in Hillsborough currently lower than in neighboring counties

- More Hillsborough County news

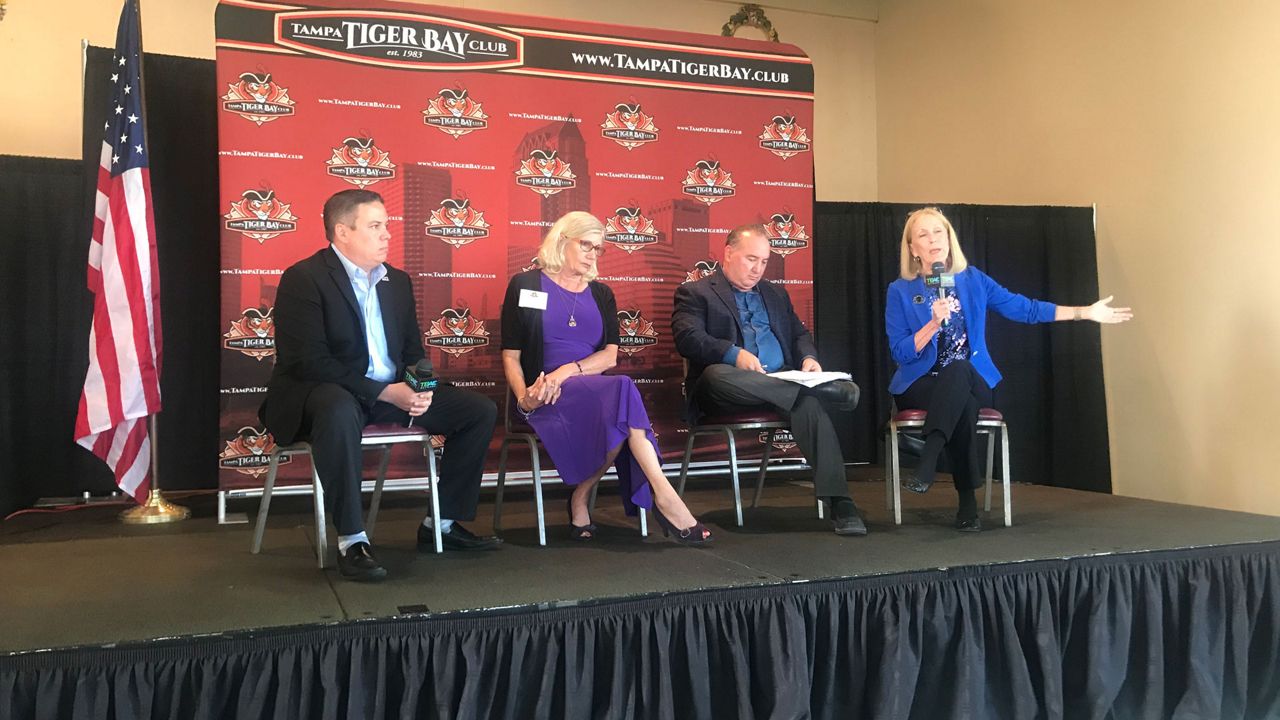

“The Politics of Growth” was how the Tampa Tiger Bay Club labeled their discussion at the Cuban Club in Ybor City on Friday. It took place as hundreds of thousands of new residents are expected to move to Hillsborough County over the next 25 years.

“We are at an important crossroads,” said Hillsborough County Commissioner Mariella Smith, a Democrat who was elected in 2018 on a “smart growth” platform that included raising impact fees. “We are going to need to figure out how many people we can afford to invite and make sure that this growth is paying its fair share of all of that infrastructure – roads, water, schools, fire, sheriff, all of it.”

The election of Smith and Kimberly Overman to the board gave Democrats a majority on the seven-member Board of Hillsborough County Commission for the first time in more than a decade, and they appear to have the votes to raise impact fees on developers for the first time since 1987.

In response to the explosive growth in south Hillsborough County, the commission imposed a nine-month moratorium on rezoning applications for parts of southern Hillsborough County last fall.

Phase fee increases in?

Steve Cona, the president & CEO of Associated Builders and Contractors Florida Gulf Coast Chapter (and a member of the Hillsborough County School Board), said his members were prepared to see impact fees raised, but said that it was important that those fees be phased in.

“We need to look at those fees, look to tier them in, because you can’t really just try to play catch-up in one year,” he said, adding it’s not just impact fees, but mobility fees and fees for site development that developers are contending with.

Smith responded that the county is losing roughly $10,000 on impact fees on every house currently being built.

“I’m not really that excited about phasing it in as about taking that cost off the taxpayers' back,” she said.

Impact fees in Hillsborough are lower than in neighboring counties like Manatee and Pasco.

Vivienne Handy, a South Hillsborough business owner and community activist, says she’d like to see the local citizenry get more involved in land use issues, but says the system works against that happening.

“We currently have a rezoning and land use process in this process in the county that is so unfriendly and ridiculous for citizen involvement,” she said. “It’s just not user friendly.”

Opinions on issue not unanimous

While most members in the audience appeared to be in agreement with Smith that developers need to start paying their fair share after three decades, it was hardly a unanimous opinion.

Jennifer Motsinger, executive vice president of the Tampa Bay Builder’s Association, said that the majority of services that the county provides have been funded from the growth that has brought in more property taxes over the past few decades. She wondered that if that growth slowed down in a year, would the county consider raising millage rates. (The city of Tampa raised their millage rate for the first time in 29 years in 2017).

Smith disagreed with Motsinger’s premise that new growth was a substantial part of the county’s budget.

“Ad valorem taxes have been $800 to $900 million a year, and the new development is two percent of that,” she said. “So you’re looking at $16-$18 million a year. That doesn’t even widen the road for half a mile.”

Regarding urban sprawl, Tampa City Councilman Joe Citro complained about the fact that he said that there are 150,000 people driving into Tampa to work. Cona reminded him that there is a remedy in the funds that are supposed to come to the county's coffers after the passage of the one-cent transportation sales tax last November.

However, because of the ongoing litigation regarding the tax, there is currently $20 million being collected every month that he said is “sitting on the sidelines.”

The lawsuit seeking to overturn the tax is slated to go before the Florida Supreme Court next month. It was estimated to raise more than $280 million annually, but those funds remain unavailable pending the high court’s decision.