LAKELAND, Fla. — Aaron Eberhardt has always wanted to help run a baseball league for the differently-abled.

“It’s been in my heart to start a league for special-needs players,” says the 38-year-old Lakeland, FL resident. “I was looking into different ways to start that. A lot of it required a lot of money, like having a special facility built. It just wasn’t feasible.”

What You Need To Know

- The Alternative Baseball Organization offers sporting opportunities or the differently-abled ages 15 and up

- The league is currently expanding nationwide

- Lakeland league manager Aaron Eberhardt is helping build teams in Florida

- The program relies on sponsors, volunteers, and donations to help those with autism and other disabilities

Baseball is in Eberhardt’s blood. He played throughout his entire young life until an injury sidelined him at the college level. The whole time he was playing, he was distressed to watch others who loved the game as much as he did forced out of it due to physical and social factors as the level of competition (and status) rose along with the athletes’ ages and experience.

“I saw a lot of friends of mine in school that were bullied by the jocks,” he says. “Maybe they were overweight, maybe their skill level just wasn’t up to par, maybe they didn’t have the self-esteem at the time...I’ve seen people just get crushed. I had a really good friend who was a catcher, he was overweight. He was good but once we got to the higher levels in high school, those other players just ate him up. It sucks watching that, you know? And there’s just no alternative.”

Nearly nine years ago, he started the Central Florida Amateur Baseball League for that very reason—to give the adults who enjoyed simply playing ball above all else an authentic format for doing just that.

“I created the league for those players, anybody who loves the game but wasn’t able to play it [at a seriously competitive level],” says Eberhardt. “It was always for the players who just want to have a good time, love the game. Skill level doesn’t matter, just go out and play the game you want to play. For those three hours, that was their time to make them feel like a star.”

As the CFABLE grew to include some 30 teams, Eberhardt noticed more and more next-level players—”college players, ex-pros that got hurt or got let go”—filtering into the mix. His solution to the problem of giving those athletes a place to play without ruining the less-skilled players’ good time was to split the league into two divisions, “Recreational” and “Competitive.”

He also started looking at the other end of the spectrum, in order to support another underserved segment of the community.

“I’ve always wanted to give to the special needs community, help out in any way,” Eberhardt says. “And I felt baseball was my strength, that’s what I grew up playing.”

His search led him to Taylor Duncan of Dallas, GA, and the Alternative Baseball Organization.

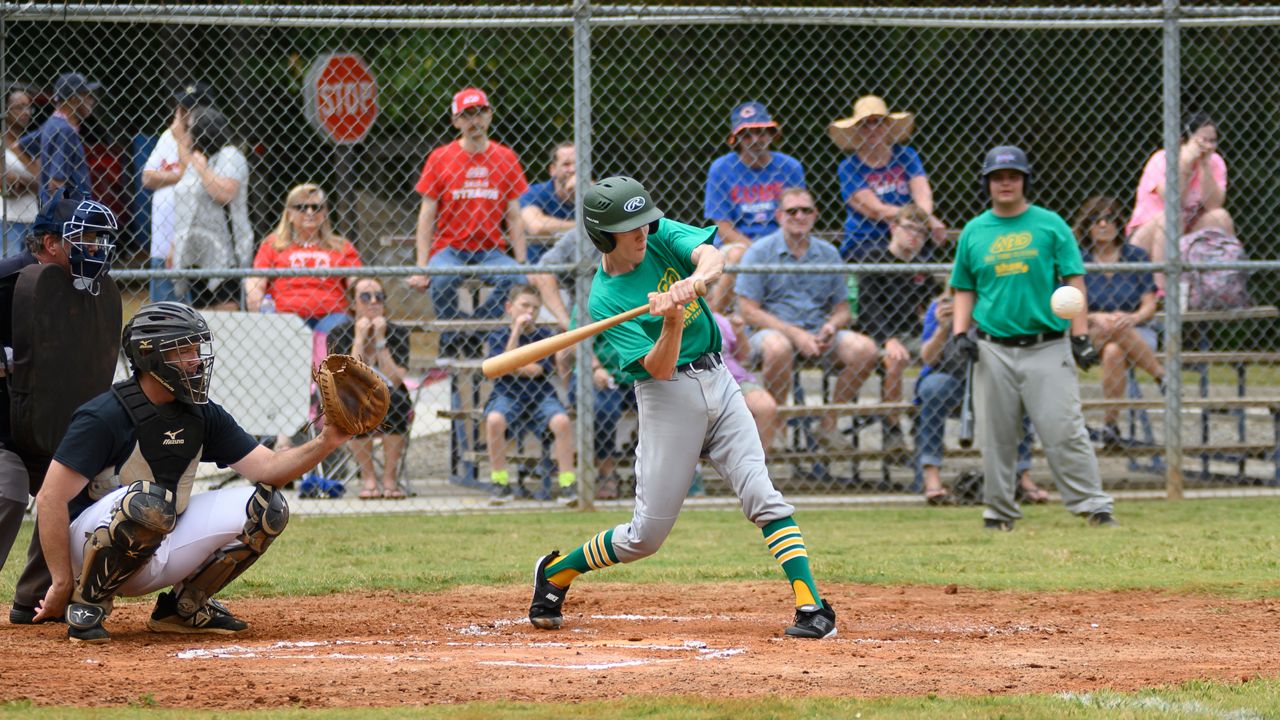

Twenty-five-year-old Duncan founded the Alternative Baseball Organization in 2016 to create an opportunity for boys and girls 15 years and older with autism and other disabilities to play “real” baseball and develop the life and social skills that organized sports help build.

“It was pretty much local at first,” says Duncan, who is himself autistic. “Then ESPN and The Today Show contacted us, and basically what was a local campaign turned into fulfilling a national need, because those in our niche demographic, once they graduate high school they just don’t have the resources they need to continue on their path to independence.”

The ABO now has around 80 teams spread throughout 33 states; while the COVID-19 pandemic put a lot of the games to a halt, Duncan credits the downtime with allowing the league to expand exponentially, as putting a team together from scratch can take up to six months. The program adheres as closely to Major League Baseball norms and rules as possible, though players come in at their own skill level.

“[Duncan] basically plays the game like normal,” says Eberhardt. “There are the one or two scenarios where there might be some players in wheelchairs, or maybe the learning curve is not as high, or maybe they do need to hit off the tee, or have underhand pitching.”

“It’s the perfect pace for everyone,” Duncan says. “You don’t have the ball-hogging issue like you do in other sports. And I grew up a big fan through the years myself, and I just didn’t have the opportunities to play like everyone else did. I had to work two or three times as hard to learn the skills.”

The league operates as a nonprofit, funded primarily through donations. Volunteers act like independent contractors, running teams as franchises in a larger network.

“We help provide them resources and rule structure, and we help provide equipment,” says Duncan. “It’s an opportunity to build relationships, social skills and really learn how to become motivational leaders through this team setting.”

The Alternative Baseball Organization is currently expanding into Florida’s Tampa Bay region, among multiple other areas nationwide (including the Orlando area), with Eberhardt as point man. Teams are coming together in Polk, Hillsborough, Pinellas, Pasco, Hernando, and Manatee Counties, and folks on the ground are looking for volunteers, donors, and fields to play; Duncan and Eberhardt hope that, as COVID vaccines continue to roll out, the league will be hosting games by this summer.

“I’m trying to build the connections,” says Eberhardt. “Who can I reach out to in order to get the players? What I’ve been trying to do really is find contacts. I’ve been trying to kick this thing off for probably the last five years.”

“We just appreciate all the help we can possibly get from the community,” Duncan says. “After they graduate [high school], services kind of plateau, and a lot of these people don’t feel like there’s anything that fits their needs. A lot of them get sequestered, they go into seclusion and are never heard from again. That’s not a way that I know anybody would actually want to live. We all want to be accepted."